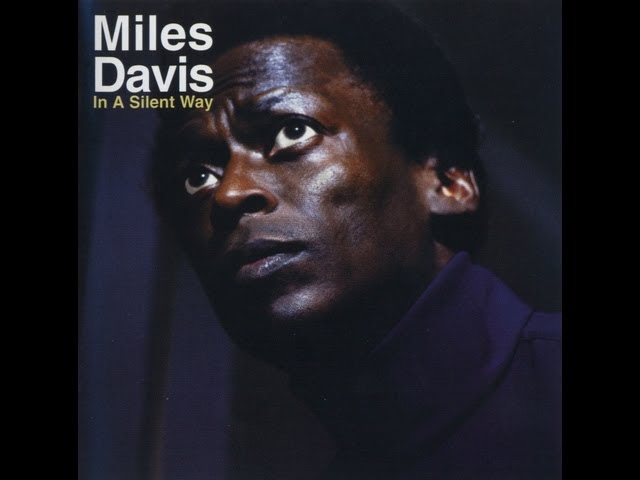

It seems odd that the first music that Miles released during his electric period should be so hushed and introspective, so…quiet. Of course, hushed was his signature voice, with a couple of by-then legendary recordings to prove it: Birth of the Cool in 1949, Kind of Blue in 1959. In 1969, when the world seemed to be getting louder and angrier and violent by the day, it was as if he knew what was most needed at the moment: a sonic balm, an emotional coolant. “[In A Silent Way] is the kind of album that gives you faith in the future of music,” wrote one critic at the time, calling it “space music” and praising its “reverent, timeless realm of pure song.”

In A Silent Way proved to be both timely and timeless. Recorded in February 1969 and released on LP as two side-long jams, it introduced ideas that what would become common to many of Miles’ albums in the years ahead: a rotating cast of sidemen that changed track by track, which meant—at least on studio recordings—the idea of a consistent band was no longer a priority. New names swung into Miles’ orbit, each bringing a new sound and sometimes instrument, for one tune, perhaps to return on another album.

Wayne Shorter—focusing on the soprano saxophone exclusively for these sessions—Chick Corea, Dave Holland, and Tony Williams were all in place, along with Herbie Hancock and Joe Zawinul—an alumnus of Cannonball Adderley’s band—also on electric keyboards. The most notable of the new additions was another British import: John McLaughlin on electric guitar. His lines define the melodies—an impromptu pattern he created in the studio served as the theme of the title track—and his solo statements deepen the mood. While he would reveal the grit and bite he was capable of on later Miles recordings, on In A Silent Way McLaughlin was about understatement and taste.

Miles had met McLaughin by way of Williams, who had joined with the guitarist and organist Larry Young in creating his own plugged-in, amped-up jazz trio—Lifetime—which Miles had eyes on absorbing into his own tours and projects. Williams, already planning to exit Miles’ band, balked at this idea; the tension this caused apparently led to his atypically subdued playing on In A Silent Way. Whether apocryphal or not, elements of this story are true, and Williams’ drumming does in fact dovetail with the overall vibe.

The album’s most unconventional idea was its most controversial, at least with some critics. It was hard to miss that In A Silent Way—especially the track “Shhh/Peaceful”—included repeated spliced sections, the same performance looped in post-production. While this idea seemed an anathema in the jazz world of 1969—even overdubbing was frowned on back then—this innovation predicted the present-day, cut-and-paste approach to constructing final recorded product. Teo Macero, Miles’ longtime producer at Columbia, had the edit-room savvy to make it happen. Most significantly, Miles was OK with it.

It was the calm before the electric storm of Bitches Brew.